The Rule of Three: Survival Essentials

Jan 17, 2026

Jay

Survival Skills

You can call it a rule, a guideline, or an old field note passed from one survival instructor to the next. In practice, the Rule of Three has never been about the numbers themselves. It exists to answer a far more important question: What matters first, when things stop going according to plan?

Most accidents don’t happen because people lack strength, gear, or even knowledge. They happen because priorities slip. Stress compresses time, narrows judgment, and shifts attention to the wrong problem. In those moments, survival isn’t about doing more, it’s about doing things in the right order.

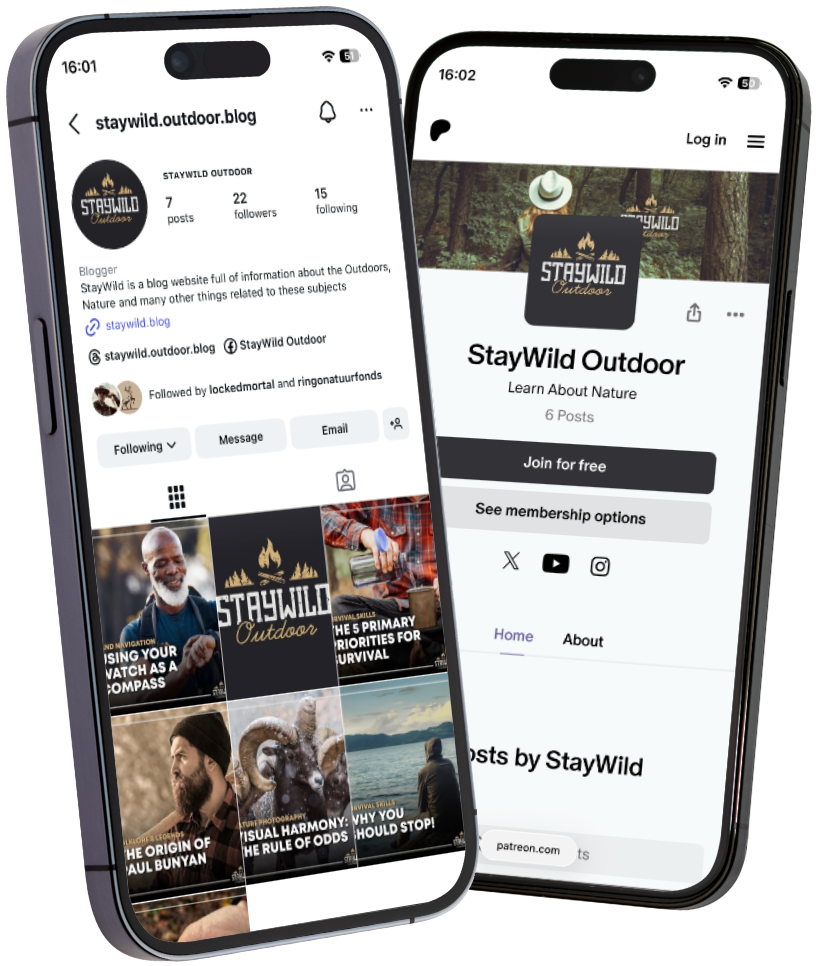

The 5 Primary Priorities for Survival

Survival Skills

We’ve already talked about the 5 Priorities in Survival, which is a good skill to know, but to lift this skill to a new level is to know what the urgency of your priorities are. And this is where the Rule of Three comes in.

Survival Is a Matter of Priority

We often imagine survival as a series of dramatic, split-second decisions. Sometimes that’s true. But far more often, situations deteriorate slowly because attention is misplaced.

Many outdoor incidents escalate not because the environment suddenly becomes hostile, but because people invest time and energy in low-priority tasks while high-priority threats remain unresolved. The Rule of Three acts as a corrective, a mental checklist that forces order when stress tries to take it away.

In most iterations of the “rule” they discus how long a person can go without air, shelter, water and food. But in complicity there are actually two more that can greatly impact your state of survival.

- 3 seconds without hope

- 3 minutes without air

- 3 hours without shelter

- 3 days without water

- 3 weeks without food

- 3 months without human contact

Trying to remember this list, can become the difference of struggle or survival.

The Rule Isn’t Accurate, and That’s the Point

No serious instructor will claim these timeframes are exact. People have survived without food for over forty days. In one well-documented medical case, Angus Barbieri lived for more than a year under strict supervision on nothing but water, vitamins, and non-caloric drinks.

Even though the rule is not completely accurate. When you find yourself in harsher environments your time without shelter might be shorter. Or if you have a peaceful location, not even necessary. The inaccuracy of doesn’t weaken the Rule of Three, it explains it. The rule is more about a general guidance. It isn’t a biological countdown. It’s a priority ladder. It reflects how fast certain problems become irreversible if ignored. Environment, weather, fitness, and experience all shift the margins, but the sequence remains sound.

Mindset: Where Survival Actually Starts

The first and last elements often added to the rule, hope and human contact, point to something many survival discussions avoid: mental stability is not optional. Stress clouds our judgment, increases fatigue and can lead to even fatal mistakes. So try to stay focused and be calm.

In that same vain, humans are inherently social creatures. We can tolerate being alone, sometimes even seek it out, but overal; we can’t really function without social feedback. Over time we’ll suffer from reduced problem solving flexibility, we can gain tunnel vision on decision making and even an increase in rumination resulting in a poor risk assessment.

Trying to keep ourselves sane and hopeful is a good starting point for our survival. This also doesn’t mean solo travel is unsafe. It means that structure, routine, and mental engagement become critical when contact is limited. Survival begins in the head long before it shows in the body.

From Minutes to Weeks: The Physical Realities

Loss of oxygen is one of the few survival threats that allows almost no margin for correction. Drowning, entrapment, smoke, or toxic gases can render a situation fatal in minutes. In fires, for example, people rarely die from burns. Smoke inhalation and oxygen deprivation do the damage first. Even a poorly ventilated shelter or campfire can introduce dangerous levels of carbon monoxide. Air isn’t dramatic, it’s absolute.

Once breathing is secured, exposure becomes the next decisive factor. Wind, rain, cold, and heat don’t kill instantly, but they erode energy and judgment quickly. Shelter doesn’t mean comfort. It means reducing heat loss or heat gain to a level the body can manage. Sometimes that’s a roof. Sometimes it’s shade. Sometimes it’s nothing more than a windbreak and dry ground.

Dehydration degrades performance long before it becomes life-threatening. Poor decisions, fatigue, and confusion appear first. Water management is as much about pacing and planning as it is about finding a source. Just at food which, despite popular belief, is rarely an immediate survival concern. Lack of calories affects morale and long-term endurance, but it doesn’t demand urgent action in the first days of an emergency. Hunger is uncomfortable. Exposure is dangerous. The Rule of Three exists to keep that distinction clear.

Why the Rule Still Matters

The Rule of Three persists because it works under pressure. It strips survival down to sequence in a simpel order and memorable sequence. It forces you to confront the most dangerous problems first, even when they’re boring, uncomfortable, or unsatisfying to deal with.

It reminds you not to chase solutions that feel productive while ignoring threats that quietly escalate. The Outdoors and it’s survival is rarely about toughness or improvisation. It’s about restraint, awareness, and order.

Conclusion

The Rule of Three won’t save you by itself. But it will stop you from making the kind of mistakes that turn manageable situations into real emergencies.

When stress rises and clarity drops, don’t ask yourself how long you can last. Ask yourself what actually matters right now. Solve the most urgent problem first. Then move to the next.

That simple discipline has kept people alive long before the rules had a name, and it still does.